Traci Chee is one of my favorite authors to interview, and I’ve featured all three books in her Sea of Ink and Gold trilogy: The Reader, The Speaker, and The Storyteller. Ever since I heard the premise for WE ARE NOT FREE, I couldn’t wait for it to come out. The book debuted yesterday, and I hope all libraries can find a place for it on their physical (and virtual!) shelves:

“All around me, my friends are talking, joking, laughing. Outside is the camp, the barbed wire, the guard towers, the city, the country that hates us.

“All around me, my friends are talking, joking, laughing. Outside is the camp, the barbed wire, the guard towers, the city, the country that hates us.

We are not free.

But we are not alone.”

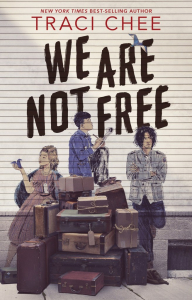

From New York Times best-selling and acclaimed author Traci Chee comes We Are Not Free, the collective account of a tight-knit group of young Nisei, second-generation Japanese American citizens, whose lives are irrevocably changed by the mass U.S. incarcerations of World War II.

Fourteen teens who have grown up together in Japantown, San Francisco.

Fourteen teens who form a community and a family, as interconnected as they are conflicted.

Fourteen teens whose lives are turned upside down when over 100,000 people of Japanese ancestry are removed from their homes and forced into desolate incarceration camps.

In a world that seems determined to hate them, these young Nisei must rally together as racism and injustice threaten to pull them apart.

In our last interview, you said, “Try to celebrate every step of the journey, because every step is leading you where you need to go.” What part of your journey initially felt like a setback, but turned into a step forward?

Ah, for this question, please allow me to take you back in time to 2014. I’d finished the first draft of The Reader in January—at midnight on New Year’s Eve, to be exact!—and after a few months of revising and polishing it up, I thought, “Well, this is as good as I can get it all on my lonesome. Time to query!”

Reader, I was wrong.

I sent out maybe twenty queries in small batches, and one-by-one, they all came back with rejections. Most were form rejections. A scant few were rejections-on-partials. And it hurt. It filled me with doubt. It made me question whether or not I should even bother continuing.

So I stopped… or at least I stopped querying. And I sought help. (Most notably, I submitted my query for a free critique from Adam Silvera and Jasmine Warga, who were for one serendipitous weekend generously offering their help to those of us still in the query trenches.) I took a good hard look at my query and my manuscript. And do you know what I discovered?

It wasn’t as good as I could get it all on my lonesome. There was still so much work to do. (Most notably, at 121,000 words, it was way too long for a debut YA fantasy.) And I needed to take the time to do it.

So I did. I spent the next few months excising thousands of words from that manuscript, tightening the plot, developing the characters, and by summer, I had 14,000 fewer words and a much better book on my hands. It still wasn’t ready for publication—I could tell by then that I had more work to do—but I knew it could be ready for Pitch Wars.

Now, Pitch Wars was (and still is) an online contest in which unagented writers apply to work with mentors to revise and hone their manuscripts and queries. Not everyone gets an agent through it, but for me, that wasn’t the point. I wanted to work with a mentor. I wanted to work with someone who’d been through the querying process, who knew the market, who could help me whip my book into shape.

I wanted to work with Renée Ahdieh.

And I was so fortunate that she picked me as a mentee, because with her suggestions and under her guidance, I was able to cut another 10,000 words from my manuscript, streamline the plot and characters, and, in general, write a better book. By the end of that two month mentorship, I had a manuscript that was actually, finally, in querying shape.

And I wouldn’t have gotten there—or at least I wouldn’t have gotten there as quickly—without those initial rejections, without that doubt, without the question of whether or not I should continue. Getting twenty rejections (which is, all things considered, a relatively small number) may have felt like a setback at the time, but it also pushed me harder. It made me seek out help. It made me a better judge of my own work. It brought me to a peer group, many of whom I’m still friends with today, and it set me on a clear path toward publication. Most of all, it made me a better writer, and for that—and so much more—I am eternally grateful.

Knowing whether or not a novel is in query shape is a definite skill–thank you for sharing your journey in that regard! WE ARE NOT FREE offers a lot of different points-of-view. What was the most challenging part about weaving together so many different narratives?

We Are Not Free is a novel-in-stories about a group of Japanese American teenagers whose lives are irrevocably changed by the US mass incarcerations of World War II. There are fourteen different main characters—roughly one chapter for each of them—and if I could have written it any other way, I would have! The thing is that this book had to be a novel-in-stories. The Japanese American incarceration is part of my family history—my grandparents and their families were incarcerated for three years during World War II—and for the longest time, I knew I wanted to write about it. I just didn’t know how. Because how could I possibly hope to illuminate all the complexities of that time period, all the nuances and contradictions and disparate experiences, in a single story? A single character? There was just no way.

But then I realized I didn’t have to write just one story. And once I understood that I could use different characters to delve into the different parts of the incarceration, from the mass eviction of Japanese Americans from the West Coast to the conditions in the camps to the so-called “loyalty questionnaire” that divided the community, I knew that with so many perspectives, I could create this kaleidoscope of experiences, every one illuminating a new part of the incarceration.

Figuring out how to connect fourteen different perspectives—fifteen if you count the chapter in first-person plural—was one of the most difficult parts of it for me. I had to make each chapter self-sustaining, so that it could stand on its own, while also linking it to all the others in a way that created not only a series of satisfying stories but also a satisfying novel-length arc with its own beginning, middle, and end.

And for me, the answer came in love. These characters, for the most part, have known one another all their lives. They’ve grown up together on the streets of San Francisco. They’ve gotten into trouble together and fought together and helped one another out when times were tough. They are like family—some are actually family—and they love one another with such ferocity that that connection is what links them all, even as they’re evicted from their homes, even as they’re shipped off to high-desert camps and deployed overseas. In the first chapter, for example, we have Minnow, who introduces us to his older brother Shig. And in the second chapter, we have Shig, who introduces us to his girlfriend Yum-yum. And in the third chapter, we have Yum-yum, who introduces us to her best friend, Bette… and so on and so forth. Each character loves the one that came before and the one that comes after, and so the entire novel is like this chain of adoration and admiration and dedication that sustains these teenagers through some of the hardest, most difficult moments of their lives.

What a poignant way to connect all these beautiful stories together. What do you feel are the necessary elements of a good story?

Actually, I don’t think there are any necessary elements. I’ve read good stories without plots. I’ve read good stories without characters. I’ve read good stories with high stakes and good stories with low stakes. I’ve read stories where nothing happens, or nothing happens except in the mind of the narrator, and good stories where everything happens, or everything begins or everything ends. I’ve read good stories where the words are just there to tell the story and good stories where the words are the whole point of the story. I’ve read good stories that are highly enjoyable but also ultimately forgettable and good stories that I’d never read again but stick with me for decades.

Maybe that’s not helpful as far as writing advice goes, but I think what this means for writers is that we can be bold. We can learn the conventions of a genre, absolutely. We can study the canon, sure. We can hone our skills. We can understand the “rules.” Yes. All of these things. But also? At the same time? We can be adventurous. We can try new things. We can fail. We can try them again. And again. We can push boundaries. We can write drivel. We can keep learning. We can adhere to conventions… or not. We can abandon or keep what’s useful to a particular project at a particular time. We can interrogate what a “good story” is and discover what that means anew and again, anew and again, anew and again.

![]() Buy: Bookshop.org ~ BookPassage ~ Amazon.com ~ Barnes & Noble ~ IndieBound

Buy: Bookshop.org ~ BookPassage ~ Amazon.com ~ Barnes & Noble ~ IndieBound

Buy: Bookshop.org ~ BookPassage ~ Amazon.com ~ Barnes & Noble ~ IndieBound

Buy: Bookshop.org ~ BookPassage ~ Amazon.com ~ Barnes & Noble ~ IndieBound

Buy: Bookshop.org ~ BookPassage ~ Amazon.com ~ Barnes & Noble ~ IndieBound

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!